Food ingredients

This article was originally published in June 2013

Mainstream supermarkets carry an average of more than 38,000 different items with more than 10,000 chemicals sprinkled among them. The Hostess Twinkie, for instance, is famous for having 37 ingredients, including several powder-based chemicals and vague “natural and artificial flavors.”

If the inquisitive shopper doesn’t understand what a specific ingredient is, how it is made, or what its purpose is, what assurance do we have that every ingredient on a label is safe to eat?

“Generally recognized as safe”

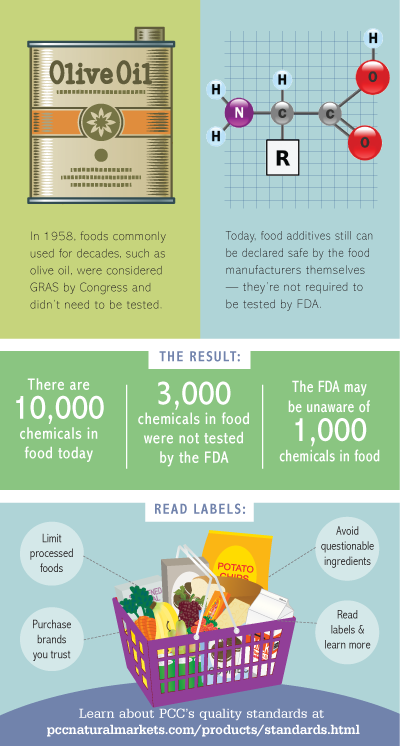

The Food Additives Amendment of 1958 was intended to ensure chemicals added to food were safe. Congress created an exception, however, for food ingredients that had been used commonly for decades and, at the time, did not believe they needed to be tested thoroughly. Industry was given authority to declare such ingredients (e.g. olive oil and vinegar) “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS).

Manufacturers today have moved well beyond the law’s original intent. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Food Additives Project, manufacturers regularly use the GRAS process to declare the vast majority of new additives safe, rather than submitting them for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. What was intended as an exception has now become the de facto rule.

That’s worrisome for consumers who expect ingredients are tested independently before being allowed on the market. It’s also troubling because there’s no systematic reassessment of chemicals. Once a chemical is deemed safe, it’s very difficult to change that status.

Tom Neltner, director of the Pew project, says, “Pesticides have to get reviewed for safety by the Environmental Protection Agency every 15 years. They just went through a massive review of over-the-counter drugs at FDA.” In contrast, he says, “it’s often very hard to change the status of a chemical.”

The complexity of our food supply and the oversight of its safety raise fundamental questions about what we eat. The following FAQs summarize Pew’s peer-reviewed findings about the U.S. food regulatory system.

- Who approved the 10,000 chemicals?

Manufacturers or trade association panels approved more than 3,000 of the estimated 10,000 substances allowed in human food without any FDA review. Of those, Pew estimates about 1,000 chemicals are unknown entirely to FDA and the public. An informal survey of food industry experts suggested the figure could be significantly higher. - Who regulates chemicals in our food?

FDA is the primary federal agency that regulates chemicals added to our food, including food additives, color additives, and drugs used in animal feed. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) oversees pesticides used on food. - Are there restrictions on what chemicals can be added intentionally to human food?

Yes, there are restrictions. A safety determination is required before a chemical can be allowed in our food. However, a company can make its own determination that a chemical is generally recognized as safe and clear it for use without notifying FDA or the public. -

How do most chemicals receive clearance to be added to food?

There are three ways a food manufacturer can get clearance to add a chemical to its products:- Self-determination: In 1958, Congress allowed a manufacturer to decide on its own that a chemical’s use is GRAS. This determination should be based on the opinion of experts who “have to actually be qualified to understand the field,” says Pew’s Neltner. “But you don’t have to have a scientific panel look at it.”

“The law,” he says, “does not prohibit a company employee from making a determination of safety. The only thing the FDA insists on is that there be published studies.”

Neither FDA nor the public are involved in the safety decision, and they do not necessarily know about the chemical and in what foods it’s used. - Petition: FDA approves the use of a chemical in response to a petition by a manufacturer and provides opportunity for public comment before the chemical is approved. Before 1995, FDA conducted all of its food additive reviews this way. But from 2006 to 2010, this process accounted for less than 3 percent of the agency’s reviews.

- Notification: A manufacturer asks FDA to review its safety decision for a chemical’s use. If the agency’s review raises no concerns, FDA sends a letter stating that it has “no objections” or “no questions” to the manufacturer’s decision without any opportunity for public comment.

If the agency raises concerns, a manufacturer may withdraw its notification but still is able to use the chemical via the self-determination process. FDA instituted the notification approach in the late 1990s. From 2006 to 2010, more than 97 percent of the chemicals were cleared using this method.

Neltner told Food Safety News that unlike the petition process, which allows for public comment, the GRAS notification process does not. “The notice and comment is taken away and [FDA’s] requirement to respond to comments is gone. So you don’t get the input of academics. You don’t get the input of competitors.” For consumers, he says, “that’s a drawback.”

- Self-determination: In 1958, Congress allowed a manufacturer to decide on its own that a chemical’s use is GRAS. This determination should be based on the opinion of experts who “have to actually be qualified to understand the field,” says Pew’s Neltner. “But you don’t have to have a scientific panel look at it.”

- Why would a company choose the notification option if it could just self-determine a chemical’s safety?

Manufacturers sometimes choose to seek FDA review rather than pursue self-determination because the agency’s no-objection or no-question letter helps with product promotion.

Companies have been known to market the letter as FDA approval, even though the agency maintains it is not. - What are the concerns with a company’s ability to self-determine the safety of a chemical without notifying FDA?

There are two chief concerns. First, if FDA is not aware of a chemical being used in our food, it cannot ensure a company used sound science to evaluate its safety. Second, an industry scientist may have a conflict between the company’s economic interest in getting a new product to market and its responsibility to ensure its customers are safe.

Additionally, many chemicals used in food are not required to be listed on the ingredient list. This means we often may not know what chemicals we are eating.

Marianna Naum, in the Office of the Deputy Commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine, takes issue with that point. “There aren’t a lot of ingredients that FDA is unaware of,” she told Food Safety News.

“It is important,” she says, “for us to keep in mind that these ingredients aren’t necessarily new ingredients. We are just finding a new use for [them]. I think it is a misconception of the GRAS program. These are mostly old ingredients used in new ways.” - Does FDA ensure the continued safety of a chemical after it has been cleared?

When Congress established the food additive regulatory program in 1958, lawmakers focused on ensuring a chemical was safe before use. Congress did not require FDA regularly to review chemicals added to food after their initial approval. As a result, FDA only reassesses past decisions on a case-by-case basis, usually in response to petitions from industry or public interest organizations.

The last and only systematic review of chemicals added to food was ordered by President Richard Nixon in 1969 and covered just a few hundred chemicals. This review ended in the early 1980s. The agency has not acted on 18 of the chemicals where concerns were raised.

Even if new evidence emerges suggesting a chemical in use could harm consumers, FDA has difficulty requiring industry to conduct tests on potential risks. In addition, food manufacturers generally are not required to alert FDA to new studies that raise questions about a chemical’s safety.

Manufacturers have no incentive to conduct post-market studies to ensure their chemicals still can be considered safe. They must report only adverse health effects in cases of death and serious harm, which FDA has not defined. On the whole, these limited reporting requirements make it difficult for FDA to ensure chemical additives may not cause long-term harm to people.

These findings understandably may leave consumers frustrated that the U.S. food regulatory system is weak and lacking transparency. As more ingredients are introduced, the FDA must face increasing responsibilities with dwindling resources.

“These are very complicated issues, Neltner says. “The law hasn’t been revised in the last 50 years. … And [FDA] is an office that keeps getting more and more work.”

This article is based on excerpts and quotations from the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Food Additives Project and the article, Food ingredients: Many routes to safety approval, which was published in December in Food Safety News.