Robots in the milking parlor

by Ariana Taylor-Stanley

This article was originally published in December 2014

Washington’s organic dairies are leading the herd toward new technology.

Robotic milking machines might sound like they belong on industrialized megafarms, but the first dairy in Washington to bring robots into the milking parlor was a family-run organic farm. So was the second.

In fact, according to Aaron Johnson of Excel Dairy, of the six Washington dairy farms to install robotic milking machines so far, five are organic. As sustainable dairies turn to robotic systems, the robots are helping them to become more sustainable businesses.

The Styger Family Dairy Farm in Chehalis, which sells organic milk from its 90 cows through the Organic Valley co-op, was the first farm in the state to install a robotic milking machine system. Owners Linda and Andy Styger are nearing retirement age and none of their grown children plan to take over the farm.

“The robots give us the chance to be sustainable for at least 10 more years,” Linda Styger explains. She hopes by then her grandchildren will be ready to take over the farm. The robots will make it “easier for a family member to take over and have a better quality of life,” says Styger. “Someday we hope to make that transition for the fourth generation.”

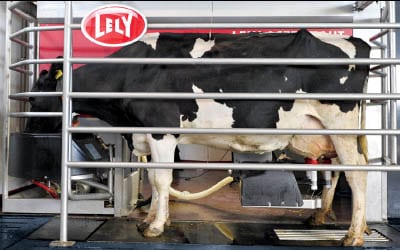

The Stygers installed their Lely Astronaut A4 robotic milking system in March 2013. The system, like most of those in use in the state, costs about half a million dollars and includes two robotic milking machines, as well as a control computer, storage tank, compressor and accessories. The Stygers expect their system to pay for itself in less than 10 years. It has saved them money on labor and vet bills, and increased milk production.

Happier cows, happier farmers

Linda Styger says the robots have changed the relationship between farmers and cows. Prior to introducing the robots, the Stygers had to “push” the cows into the barn for milking and then back out again to the pasture. The cows resented being herded, and the farmers resented the rigid milking times: 4 a.m. and 4 p.m.

With the robots, Styger says, “the cows are friendlier to us now that we are not constantly pushing them … Once you retrain them, they choose to come milk, they choose to come feed, they choose to go to pasture.”

Cows have free access to the robotic milking machine, which automatically scans and cleans their udders and attaches the teat cups before milking. The robot also tests the milk from each teat for impurities, diverting abnormal milk away from the storage tank. It collects 120 data points about each cow, which it recognizes by a transponder worn around her neck. The cows can choose to be milked up to six times per day but average about three milkings. Lely, the robots’ Dutch manufacturer, describes this as “the natural way of milking,” as it more closely approximates how often cows nurse their calves.

Big cow data

Linda Styger uses the robot’s data to monitor herd health. Sitting in front of the control computer in her office above the cow stalls, she scrolls through tables of data on each cow. Noticing one cow has a teat chronically producing abnormal milk, she makes a diagnosis — mastitis — and with a click of the mouse, tells the robot to stop milking that teat so it can recover. Styger says the farm’s veterinarian now needs to visit half as often as before the robots.

Close monitoring and management of the cows’ health is critical for organic dairies, which are prohibited by organic regulations from using antibiotics. Economic factors also have played a role in organic farms’ faster adoption of robotic milking technology. Organic farms, which tend to be smaller than conventional, require fewer robots to milk a whole herd, meaning less up-front investment. The higher prices organic producers receive also help make large investments more feasible.

An added benefit? “In the old parlor, sometimes you’d get kicked,” Styger recalls. “She can kick at this machine all she wants and it doesn’t bother me a bit.”

Ariana Taylor-Stanley farms with City Grown Seattle.