Good gut advice: eat more fiber

by Erica Sonnenburg, Ph.D. and Justin Sonnenburg, Ph.D.

This article was originally published in October 2016

There are more microbes in a teaspoon of intestinal contents than there are stars in our Milky Way galaxy. These bacteria are wired into virtually all aspects of our biology. They set the dial on our immune system, determining whether we launch an immune response to a food we just ate or when to dampen a response after an infection. They also are tuned into our metabolism, helping our body decide whether to burn or store extra calories.

Most recently, gut bacteria have been linked to the functions of our brains, potentially playing a role in our moods and behaviors. These trillions of bacteria play a key part in regulating and maintaining our overall health. But when they aren’t staving off disease, what are all these microbes doing in our gut? Eating.

The forgotten organ

The gut microbiota or microbiome, as it often is referred to, has been called the forgotten organ. The major function of our microbial organ is to consume carbohydrates. Not just any type of carbohydrate but specific microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs).

MACs are complex carbohydrates, the types found in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds and legumes. When our gut bacteria consume — or more accurately ferment — MACs, they release an assortment of chemicals that our body absorbs. The function and identity of many of these chemicals are unknown but some have been shown to modulate the function of our immune system, keeping “bad” bacteria at bay. Some contribute to whether we’re lean or obese.

What happens if you, like most Americans, don’t eat many MACs? Is your microbial organ lying in wait, famished and hopeful that you will feed it again soon? Not exactly. When your diet doesn’t contain enough MACs, your microbes are forced to rely on the only other carbohydrate source it has left: you. While this may sound like the plot of a horror movie, in fact your intestines secrete a slimy coat of carbohydrates called mucus that lines the wall of your intestine. This mucus lining is a rich source of carbohydrates that starving microbes can rely on when dietary pickings are slim. In this way many of our gut microbes are a bit like Jekyll and Hyde.

Provide gut microbes with plenty of sustenance in the form of MACs and they happily will convert them into molecules our body needs to be healthy and lean. Starve them of dietary MACs and they’ll munch on your mucus lining, inching ever closer to your intestinal wall.

Unfortunately, this scenario could set off alarm bells within your immune system that microbes are getting dangerously close to penetrating the protective wall your body has constructed to keep them — the bacteria — at a safe distance from us, our collection of human cells. The long-term ramifications of this could be an immune system that’s on a hair trigger, impacting not only the health of your gut but your entire body.

Big MAC diet

So how can we ensure we’re eating what our family jokingly refers to as a Big MAC diet? Dietary fiber is the closest approximation we have for MACs. Consuming foods that are high in dietary fiber can provide much needed nutrition for our microbial partners. But it’s clear that Americans aren’t getting enough dietary fiber.

The average American consumes a measly 15 grams of dietary fiber per day. This falls far short of the 30-38 grams recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is even further still from the 100-150 grams of fiber consumed by modern-day hunter-gatherers.

A growing number of studies have revealed that the average Western gut is housing far fewer microbial species compared to people living a lifestyle and eating a diet more similar to our early agrarian or hunter-gatherer ancestors.

If you liken the community of bacteria residing in your gut to a jar filled with jellybeans, individuals from traditional populations around the globe have a jar filled with jellybeans of various flavors and colors — a diverse mixture. The jar representing the Western gut has only a few flavors and is quite homogeneous.

It appears that as our consumption of dietary fiber has decreased, so has the number of species of bacteria living in our gut. Entire flavors of jellybeans have disappeared from our jars. To make matters worse, since much of our microbiota is passed on to the next generation, the extinction of certain species of microbes within our gut means that with each generation our collection of “jellybeans” is deteriorating further.

The health link

Scientists don’t yet know what the long-term ramifications of these gut “extinctions” might be. But as scientists who have studied the microbiota for the past 13 years, we have a hypothesis.

The simultaneous rise in diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune diseases, and even depression in our society points to a potential common thread. While these complex diseases are likely to be the result of several insults, scientists, like us, are starting to view a diseased Western microbiota as a potential major contributor.

Some have argued that the rise in so-called Western diseases is just a product of longer lifespans, thanks to modern medicine. But with the rising rates of allergies, asthma, obesity and other childhood inflammatory diseases in the industrialized world compared to essentially zero in hunter-gatherer populations, it’s hard to argue that there’s not something fundamentally going wrong with our biology.

Perhaps additional scientific research will uncover that our modern, “Western” microbiota is in fact fine and does not significantly contribute to Western disease. After all, although there are numerous studies linking a deteriorated microbiota to several Western diseases, scientists are trained to recognize that correlation does not equal causation.

Perhaps the mountain of evidence showing increased dietary fiber reduces the risk of all-cause mortality has nothing to do with the fact that our microbes require dietary fiber. But the question is, while we wait out the years or even decades of research required to draw conclusions about these unknowns, what are you going to eat? Many lines of evidence point to the standard American diet starving our gut bacteria and making us sick.

The science is clear that diet is one of the single biggest levers we have to impact our gut microbiota. Eating a diet replete with dietary fiber can help your gut bacteria focus on consuming food and not you. In practice this means each meal needs a healthy portion of fruits, vegetables, beans or whole grains so that you are consuming at least the 30-38 grams of dietary fiber per day recommended by the FDA. For example, the day could start with a bowl of steel-cut oatmeal with berries, then a kale salad sprinkled with nuts, seeds and dried fruit for lunch, and finally a dinner of a vegetable-filled Mediterranean-style bean soup. This type of diet ensures that our microbes have plenty to eat so they can maintain a robust and thriving community within our gut. So next time you sit down to a meal, ask yourself: Are my trillions of dinner guests getting enough food as well?

Good-bacteria promoting foods

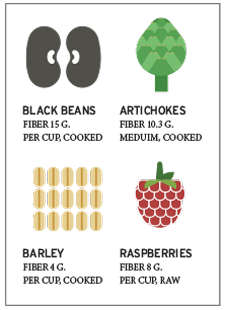

- Legumes and pulses, such as black beans, garbanzo beans and lentils are stars in the high-fiber foods category. Hummus is a great gut bacteria-boosting snack that is also very kid-friendly.

- Whole grains, such as barley, bulgur and oats have a lot of fiber, but be sure to consume them in their whole-grain form, not overly refined.

- “Bulbs”: onions, garlic, leeks, fennel and sunchokes. All high-fiber vegetables are great for the gut, but bulbs in particular have a lot of a type of MAC called inulin, which is good at promoting healthful bacteria. Celery root and burdock also are high in inulin.

- Fruits are a great source of MACs, particularly berries.

- Nuts and seeds. Sprinkle chia seeds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, almonds or chopped pecans on everything from yogurt to salads.

- Dark chocolate has an abundance of MACs. Choose high-quality dark chocolate (70 percent or above) for a treat that’s also a treat for your gut bacteria.

Important note: When transitioning to a high-fiber, gut-friendly diet, it is important to take things slowly to allow your gut to adjust to the newfound abundance of MACs. Start by slowly ramping up the amount of fiber in your diet. You may notice an increase in the amount of gas production (remember, gas is a sign that your gut bacteria are hard at work). Over time the community in your gut will adjust and gas production will normalize. There is an old Mexican adage that the cure for an intolerance of beans is a steady diet of beans!

Erica Sonnenburg, Ph.D., is a senior research scientist in microbiology and immunology at Stanford University School of Medicine. Justin Sonnenburg, Ph.D., is associate professor in microbiology and immunology at Stanford University School of Medicine. The Sonnenburgs are co-authors of “The Good Gut: Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health,” available for sale at PCC stores.