Eat organic, lower cancer risk by 25%?

by Rachel Benbrook and Charles Benbrook

This article was originally published in March 2019

A new study adds cancer prevention to the already long list of organic benefits. What will it take to accelerate the U.S. transition to organic?

Imagine the excitement if a pharmaceutical company announced the discovery of a new drug that could cut the incidence of breast cancer by 15 percent. Or, even better, imagine a major breakthrough in cancer prevention, such as a way to reduce precancerous cell growth while strengthening the immune system’s ability to stop tumor progression. Suppose such a breakthrough was shown to result in an overall 25 percent reduction in cancer risk.

Wouldn’t such a powerful new way to lower cancer risk be embraced widely and pursued in all ways imaginable? Not necessarily.

Consider the muted response in the U.S. to findings of a sophisticated, large-scale study of French citizens published in the prestigious scientific journal, JAMA Internal Medicine in late 2018.1

The study

More than 68,000 people participated in the study. On average, they were 44 years old and 78 percent were women. Participants provided detailed demographic, lifestyle, family, diet, physical activity and medical records through online questionnaires. They also were asked how often they chose organic brands in 16 categories of foods and beverages — “never,” “occasionally” or “most of the time.” These data then were used to calculate an organic-food-intake score.

Newly diagnosed cases of cancer were recorded in the study population over follow-up from 2009 to 2014. A total of 1,340 first-incidence cancer cases were diagnosed, including 459 cases of breast cancer (34 percent of total), 180 prostate cancer (13 percent), 135 skin cancers, 99 colorectal cancer, 47 non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and 15 other lymphomas.

Scientists then divided all participants into four quartiles, ranging from highest organic food scores to the lowest. They applied standard methods to control for the impact of known cancer risk factors, such as income, smoking status and family history. They then looked at whether high organic food intake was associated with differences in cancer incidence, compared to low intakes of organic food.

The main finding was that the quartile with the highest organic food intake score had a 25 percent lower overall risk of developing cancer, compared to the low intake quartile.

The risk for some individual cancers fell even more dramatically. The rate of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (the cancer that took the life of Microsoft co-founder, Paul Allen, last October) fell by 86 percent. Post-menopausal breast cancer rates dropped 34 percent.

In response to these findings, Jean Halloran, director of food policy initiatives at Consumers Reports, said, “Reductions in cancer rates of the magnitude reported in this French study are rare and promising and provide further evidence that we can help prevent cancer via dietary and life-style changes.”

Media response

Media coverage of the French study was widespread in Europe and generally positive, but limited here in the U.S. Instead, within days, the usual suspects were circulating criticisms. They noted potential sources of bias, such as the tendency of people to over-report dietary intakes of healthy foods while under-reporting less nutritious foods. Others pointed out that people inclined to seek out organic food (and pay more for it) likely are motivated to embrace other healthy lifestyle practices and are better able to afford them.

The French team, however, deployed sophisticated methods to control for such lifestyle factors and other possible sources of bias. Did they do so with complete success? Not likely, but they did everything they could to minimize bias and control for confounding variables.

“This was a large, population-based prospective investigation and the associations with reduced risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and breast cancer are particularly notable,” according to Dr. Melissa Perry, chair of the Environmental and Occupational Health Department at George Washington University. “To further explain the link between organic food consumption, pesticide exposure, and reduced cancer risk, we need to think about how much pesticide ingestion we specifically avoid by eating an organic diet.”

Even if high levels of organic food consumption would reduce overall cancer risk by only 5 – 10 percent, that still would be a phenomenally important breakthrough.

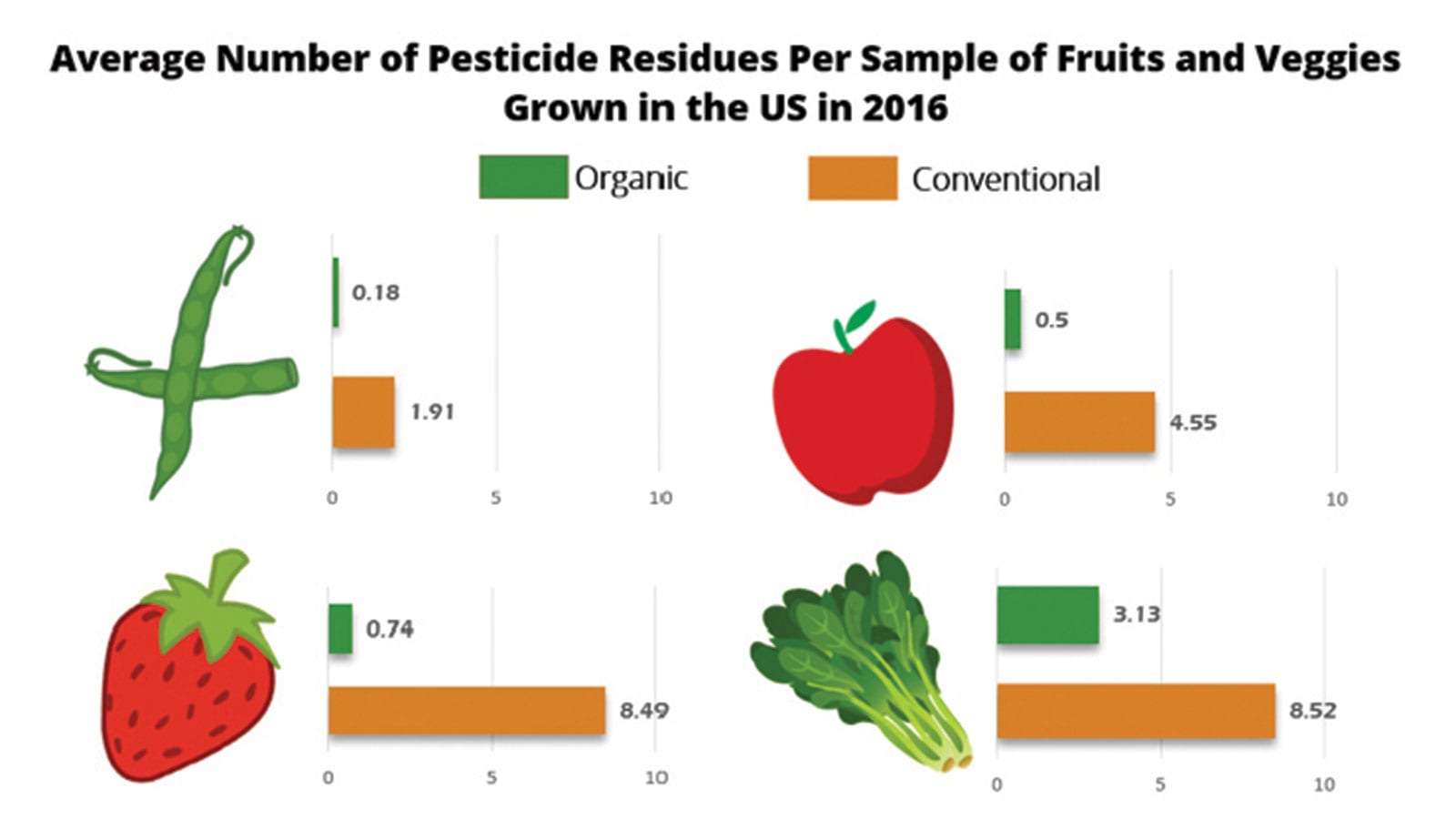

The French team points to pesticide residues in conventional food as the most plausible explanation for the health benefit reported in their study. They highlight the pesticide-cancer connection because organic farming reduces chronic pesticide dietary risk by more than 95 percent, compared to risk levels associated with the residues typically found in diets composed of conventionally grown foods (see graphic).

While residues in organic produce are much lower, they are not zero for several reasons. Post-harvest contamination in packing plants that process both conventional and organic crops is by far the most common, single source of residues on organic fruits and vegetables, accounting for more than half of the residues on organic fruit.

Another 15 percent or so of residues on organic foods are from persistent, legacy pesticides no longer used on conventional or organic farms in the U.S. About 20 percent of residues are from bio-pesticides approved for use on organic farms. Just a few percent are synthetic pesticides that should not be present on or in organic food and typically get onto organic crops via drift from nearby conventional farms or irrigation water. Only a very small percent arise from fraud or mislabeling.3

In general, the pesticide residues in organic foods are far less toxic than the mix of residues found in conventional foods. They are present at much lower levels and there are far fewer of them.

Just a few well-selected changes in diet and food selection can make a big difference in reducing a person’s exposure to pesticides. For example, a 2011 study from The Organic Center looked at how switching to organic sources for less than one-half of the items in a daily diet impacted pesticide dietary risk levels for a hypothetical 30-year old, American woman. It found that when the woman switched from conventional to organic strawberries, kiwis, blueberries, tomato products, sweet bell peppers, lettuce, cucumbers, apples and whole wheat bread and pasta, she reduced her dietary risk from pesticide exposure by two-thirds.4

For any one person, uncertainty remains over whether the pesticide residues in conventional food pose very little, modest or sometimes significant health risks. But one thing is indisputable. Whatever the risks are at each stage of life, they are far lower for those among us who consume mostly organic foods.

Other benefits

Organic plant-based foods — especially fresh produce — contain on average about 20 percent higher levels of health-promoting antioxidants, based on the most recent state-of-the-art analysis published in the prestigious British Journal of Nutrition.5 Enhanced antioxidant activity makes the daily cleanup job facing our immune systems a little easier by neutralizing “free radicals” naturally produced in our cells. This matters because these radicals cause oxidative stress, a mechanism associated with human carcinogens.

So, organic food provides two clear health benefits. First, the near-elimination of pesticide residues reduces the daily load of mutations and other cellular disruptions that can lead to or accelerate cancer. Second, higher levels of antioxidants found in nutrient-rich organic food bolster the body’s ability to limit oxidative stress.

Growing crops without toxic, synthetic pesticides also reduces farmworker risks, enhances environmental quality, saves salmon, gives pollinators a badly needed break, and builds organic matter in soil, sequestering carbon that otherwise would contribute to climate change.

With the proven capacity to deliver such impressive benefits, one would think government agencies, all farm organizations, and the global food industry would be moving heaven and earth to rapidly expand production of organic food. While close to true in some countries, the U.S. clearly is not among them.

What’s holding back U.S. organic?

The answer is not grounded in the lack of tools, technology or proven practices. It arises primarily from reluctance to change, coupled with fear of losing market share and profits.

This reticence in the U.S. to lead the global transition to more nutritious and markedly safer organic food is costing American farmers and food companies market share that would support more and better paying jobs, as well as higher prices for farmers, along with all the other, societal benefits noted above.

Unfortunately, too many people in the conventional food business see growth in the organic sector as a threat rather than an opportunity. This misperception has arisen from years of contentious wrangling between organic food advocates and conventional food defenders. This needs to change.

Organic brands are premium products that will command higher prices and will cost marginally more to bring to market. As more consumers learn about the broad benefits, investments in organic food and farming technology, human skills and infrastructure will continue to lower production costs and brighten the quality halo driving sales of U.S. food exports in many overseas markets.

Washington state could lead

It’s worth highlighting the agricultural sector in Washington state stands to gain the most of any state when the public and private sectors catch up with science and the market opportunity knocking on the door. Washington ranks No. 3 in the nation for organic farm gate sales.

From the state’s booming organic apple industry,6 to the remarkable diversity of small- and large-scale organic vegetable farms, Washington farmers and food businesses are showing the country how well organic farming systems can work when serious resources are invested in the people and infrastructure needed to capture economies of scale at all points along farm-to-consumer food chains.

New bridges supporting the transition of conventional acres to organic methods are gathering momentum and investment capital. All that’s needed to accelerate the transition is consumer demand.

PCC is doing its share and has committed to add 1,000 organic grocery products over the next five years. Imagine if the biggest corporations among us paid attention to the science and made comparable commitments.

We’re grateful to the French team for conducting such an innovative and important study. Yes, more research is needed to narrow uncertainty over the magnitude of the benefits of organic food, but it makes no sense to let the perpetual need for more research delay a transition that will leave us all better off in so many ways.

Rachel and Chuck Benbrook run Hygeia Analytics (hygeia-analytics.com) and conduct research on how agricultural systems, technology and policy impact public health and the environment.

Click here to read the original study.

How cancers develop

On any given day, oxidative stress within our cells, exposure to chemicals, and epigenetics combines to trigger roughly one million mutations per second throughout the body as our cells divide and our DNA is replicated. A small fraction of these mutations unleashes pre-cancerous cell growth.

Specialized cells in the human immune system are constantly on the lookout for mutated genes. Once recognized, they pounce and try to shut down the proliferation of mutated, abnormal cells. They do it again the next day and every day as long as we live.

For about one-third of us, there will come a day, or more likely a string of days, when our immune system is distracted, out of gas because of other environmental stressors, or just plain overwhelmed. As a result, our cellular soldiers fall short, allowing some cells with mutated, or down-regulated tumor suppressor genes to replicate and take another step closer to becoming cancer.

A few mutated genes can become several hundred quickly, and then millions and billions. Some cancers progress rapidly, especially in children with poorly developed or compromised immune systems. Others can take a decade or longer to trigger symptoms and be diagnosed, while some cancers never prove to be life threating.

Almost 2 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year in the U.S. alone and 35 percent of these cases prove fatal, despite all the tools available to target and kill cancer cells, cut out tumors, or turn off a tumor’s ability to proliferate. Experts estimate that reducing the annual incidence of cancer by just 5 percent would save 30,000 lives and cut health care costs by around $7 billion.2

- Baudry, Julia et al., “Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk,” JAMA Internal Medicine, 2018, 178:12, 1597-1606.

- Cancer statistics from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health, see: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics.

- Benbrook, Charles, & Baker, Brian P., “Perspective on Dietary Risk Assessment of Pesticide Residues in Organic Food,” Sustainability, 2014, 6, 3552-3570.

- Benbrook, Charles, “Transforming Jane Doe’s Diet”, The Organic Center Critical Issue Report, September 2011.

- Baranski, Marcin et al., “Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses,” British Journal of Nutrition, 2014, 112(5), 794-811.

- See: https://hygeia-analytics.com/special-series-the-secret-to-success-for-organic-apples-in-washington-state/