Food hubs provide “farmers market values” on a bigger scale

By Rebekah Denn

This article was originally published in October 2019

Griffin Berger’s days are more than full.

Some 15,000 trees and 3,000 vines grow on his family’s organic farm in the shadow of Sauk Mountain, from rows of the hot new Cosmic Crisp apple to an heirloom purple plum whose genetics don’t trace back to any recorded variety.

The Washington State University (WSU) graduate focuses on organic approaches to farming challenges — planting flowering “insectary strips” to attract diverse pollinators and beneficial insects, tilling in cover crops of barley and clover to control weeds and enrich the soil. He also tracks modern data on every aspect of the plantings, sending tiny apples off for nutritional testing when there’s still time to improve the final fruit, knowing that a drip irrigation system has reduced Sauk Farm’s water use by 60%.

A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) organic processing plant on the site allows workers to dry fruit into crisp snacks and press apples and grapes into cider and juice, providing new ways to maximize the harvest and reduce food waste.

“We evaluate every single thing we do…” Berger said. “We either succeed, or we learn. It’s never failure.”

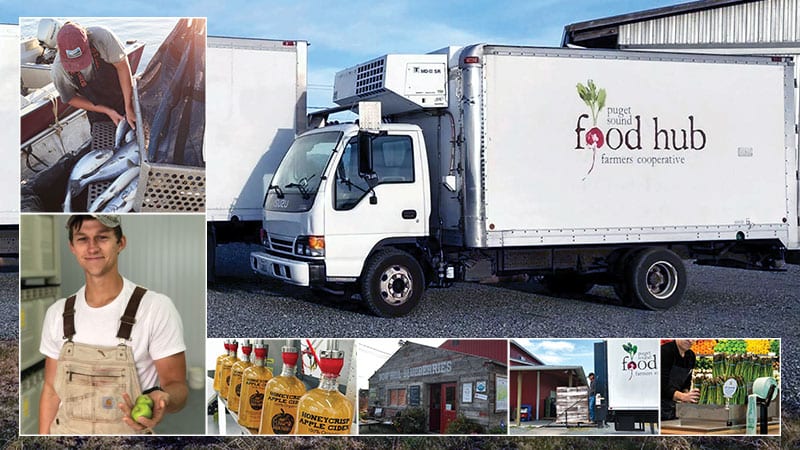

Nurturing the sweetest peaches and crunchiest apples means little, of course, if the farmers can’t sell and distribute the harvest. That’s where the Puget Sound Food Hub, a farmer-owned co-op, comes in. The hub handles orders, storage and distribution for dozens of small producers, allowing far-flung suppliers to get their fruits, vegetables and other products to regional outlets like PCC and other markets, restaurants, hospitals and commercial customers.

Hub deliveries to PCC, for instance, include not just Berger’s products, but also options like reefnet-caught salmon from Lummi Island Wild, raw unfiltered honey from Whatcom County’s Beeworks, cocktail shrubs made from Orcas Island quince and pears through Girl Meets Dirt, and frozen pizzas made with local cheese and wheat from Bellingham restaurant Pizza’zza. Few of those local suppliers could handle the paperwork, logistics and deliveries for hundreds of customers regionwide. Likewise, few commercial customers could order from the small growers without the ease of accessing their products through a single online site.

“It wouldn’t be possible” to farm the way he does without that structure, Berger said. The few accounts he services near the Concrete farm take as much time as the other 97% handled through the hub.

“The food hub allows me to specialize…” he said. “It all shows up on one piece of paper. It’s all one delivery for us.”

U.S. farms are trending toward fewer, larger properties; data from the USDA say the average farm size in the U.S. is now 441 acres and that 75% of products come from just 3% of farmland.

As pressure grows to get big or get out, food hubs are part of what Portland-based Ecotrust calls “the agriculture of the middle,” forging a path for growers who are too big to sustain their business through farmers markets and CSAs but want to sell locally rather than to global commodity markets.

“If we want to change the food system, we need to get farmers market values at wholesale scale,” the nonprofit said in a report on its efforts, which include a Portland food hub.

The Puget Sound Food Hub began in 2010 as a wholesale market in a Mount Vernon parking lot, developed with the help of two nonprofit organizations. It finalized the change to a farmer-owned co-op in 2016.

It took a lot of growth and infrastructure—a warehouse with refrigerated and frozen storage, a fleet of trucks, a sales manager—to get the hub to the point where it could serve larger customers, or markets like PCC. The original offerings of fresh products from small farms couldn’t necessarily meet those needs.

Individual small farms might, for instance, have beef available one month but not another—or might harvest enough carrots to serve 50 homes but not 500 or 5,000.

“If you’re known for an ever-changing menu, that’s a good thing at a restaurant. It’s not terrific at retail. People like a certain amount of consistency,” said Scott Owen, PCC’s grocery merchandiser.

As the hub has evolved, Owen has encouraged its addition of more year-round products, such as the organic Bow Hill Blueberries juices that farmers (and hub developers) Harley and Susan Soltes produce from 4,500 heirloom bushes in Bow.

Otherwise, Owen said, “What do you do in December and January,” when local crops are few but costs like warehouses and trucks remain?

“It’s really important to be able to expand and develop the business to something that’s 365 days a year.”

That approach is also of interest to USDA, with a report from its Agricultural Marketing Service noting that combining aggregation, distribution and marketing allows many producers to enter “new larger-volume markets that boost their income and provide them with opportunities for scaling up production.” Researchers at Cornell University suggest the hubs increase overall demand for local products, particularly “the ability to sell largely ‘rural’ products in (an) urban core.”

Already, the Puget Sound region includes hubs that are flourishing and others under development, offering different models and goals.

King County is currently investigating possibilities for a hub to serve the region.

There’s Farmstand Local Foods, with a similar model to Puget Sound Food Hub, which is based in Woodinville. In South King County, a Food Access and Aggregation Community Team is working to provide small-scale growers, many of whom are immigrants from rural communities, with ways to grow, sell and distribute culturally appropriate foods that are otherwise hard to find.

The Rainier Valley Food Bank, the region’s busiest food bank, is even looking at applying the hub model to its work as it moves into a bigger space in 2021. Their ideas include having larger food banks in the region support smaller ones, so “we reduce the amount of time we spend doing distribution in our own centers” and can focus on making foods more readily accessible, said executive director Gloria Hatcher-Mays.

The possibilities seem endless.

Meanwhile, at Sauk Farm, Berger and his small crew have time to monitor the soil moisture and beneficial insects and leaf colorations in every row they farm, figuring out which varieties work best for their land and how to nurture them. He’s thinning clusters of apples to improve the air flow on the branches, turning the unripe fruit into bottled verjus, an acidic complement to salad dressings and cocktails. The grape juice pressed from his vineyards uses wine grapes, rather than typical Concords—partly to avoid the risks of planting monocultures that are susceptible to disease, partly because he finds the flavors delightful.

“We’re trying to tweak things a different way instead of just (saying), ‘What can I spray to solve this problem?’” he said.

The way to approach farming isn’t just “how can I solve this problem,” but “What are the six things I could have done six months ago to prevent this problem?…” he said.

“You need to care about every little aspect of the ecosystem.”

And when it reaches the final stage, selling the best harvest he can for people to eat, it goes through the hub.

“Everyone wants to support local, sustainable food. How do you make that happen? The food hub is a mechanism to make that happen.”

Food hub facts

Food hubs are “an essential component of scaling up local food systems and a flagship model of socially conscious business,” according to the third National Food Hub Study released last year by Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems & The Wallace Center at Winrock International. Among the findings from the 130 food hubs who responded to the survey out of 394 invited to participate:

- More than 90% of hubs consistently state that four values are related to their mission: Improving human health, increasing small and midsized producers’ access to markets, ensuring that producers receive a fair price, and promoting environmentally sensitive production practices.

- On average, 46% of a hub’s producers and suppliers are considered beginning farmers or businesses, meaning they began business in the last 10 years.

- Food hubs appear to become more profitable over time.

- Hubs source from an average of 78 different producers and suppliers.

- Although 64% of hubs report being able to carry out their core functions without grant funding, 36% report being highly dependent on grants. Three-quarters of the hubs dependent on grants were nonprofits that may intentionally trade profitability for greater social impact.

- Forty-two percent of hubs characterized themselves as nonprofit. Another 37% classified themselves as for-profit. Consumer, producer and hybrid cooperatives accounted for 18%, and the remaining 3% were publicly owned or cited another legal structure.