Fracking and food

by Elizabeth Royte

This article was originally published in August 2013

The extraction of natural gas across America’s farmland is having devastating impacts on livestock and organic farmers, and the chemicals used may be getting into the food supply.

As the largest private landholders in areas where natural gas is abundant, farmers are approached disproportionately by energy companies eager to extract oil and gas from beneath their property. Tens of thousands of farmers, or their close neighbors, have agreed to such deals, but many are coming to regret it as their animals fall sick and die.

While scientists have yet to isolate cause and effect, many suspect chemicals used in drilling and hydrofracking (or “fracking”) operations are poisoning animals through the air, water or soil.

The costs

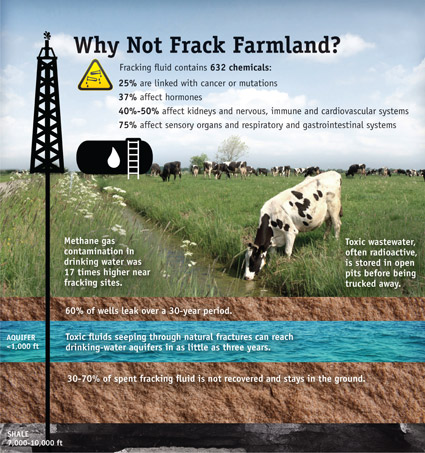

Drilling and fracking a single well requires up to 7 million gallons of water, plus an additional 400,000 gallons of chemical additives. At almost every stage of developing and operating a well, chemicals and compounds linked with cancer, mutations and hormonal disruption can be introduced into the environment.

Exposed livestock “are making their way into the food system, and it’s very worrisome to us,” says Michelle Bamberger, who authored a peer-reviewed report in “New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health” that suggests a link between fracking and neurological, reproductive and acute gastrointestinal problems in food animals. “They live in areas that have tested positive for air, water and soil contamination,” she writes. “Some of these chemicals could appear in milk and meat products made from these animals.”

Livestock illness

In Louisiana, 17 cows died after exposure to spilled fracking fluid. The most likely cause of death: respiratory failure. In New Mexico, hair testing of sick cattle that grazed near well pads found petroleum residues in 54 of 56 animals. In central Pennsylvania, 140 cattle were exposed to fracking wastewater: approximately 70 died, and the remainder produced only 11 calves. Only three survived.

In western Pennsylvania, an overflowing wastewater pit sent fracking chemicals into a pasture where pregnant cows grazed: Half their calves were born dead. Dairy and poultry operators in Colorado, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Texas also have reported the deaths of animals exposed to fracking chemicals. The death toll in fracked regions is several hundred animals.

After drilling began near Jacki Schilke’s ranch, near a fracking site in North Dakota, cattle began limping, with swollen legs and infections. Cows quit producing milk for their calves, they lost up to 80 pounds in a week, and their tails mysteriously dropped off. After five animals died, air testing detected elevated levels of benzene, methane, chloroform, butane, propane, toluene and xylene. Well testing revealed high levels of sulfates, chromium, chloride and strontium.

Schilke’s animals look healthier since she moved them away from the nearest drill pads, but she still refuses to sell them. “I don’t know if they’re okay,” she says.

Nor does anyone else. Energy companies are exempt from key provisions of environmental laws, so investigators can’t learn precisely what’s in drilling and fracking fluids. And without information on the interactions between these chemicals and preexisting environmental chemicals, veterinarians can’t pinpoint an animal’s cause of death.

Impact on food safety

The risks to food safety may be even more difficult to parse, since different plants and animals take up different chemicals through different pathways.

“There are a variety of organic compounds, metals and radioactive material (released in the fracking process) that are of human health concern when livestock meat or milk is ingested,” says Motoko Mukai, a veterinary toxicologist at Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine. These “compounds accumulate in the fat and are excreted into milk. Some compounds are persistent and do not get metabolized easily.” Veterinarians don’t know how long these chemicals may remain in animals, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture isn’t looking for them in milk or in carcasses at slaughterhouses.

While studies of drilling and fracking’s impacts on food plants and animals are ongoing, some concerned consumers aren’t waiting for hard data to tell them their meat or milk is safe. For them, the perception of pollution is just as bad as the real thing.

“My farm is pristine,” says Ken Jaffe, who raises grass-fed cattle in upstate New York. “But a restaurant doesn’t want to visit and see a drill pad on the horizon.”

Organic farmers may be worried particularly as three of the highest concentrations of organic farms are on the Marcellus shale, covering New York state, Pennsylvania and western Ohio.

Organic farmers surrounded by active wells — whether in these states or in California, where energy companies are poised to frack the Monterey Shale — are at risk of losing their certification, in addition to their confidence their fields are safe. Says Pennsylvania organic goat farmer Steven Cleghorn, “People at the farmers market are starting to ask exactly where this food comes from.”

This report was produced by the Food & Environment Reporting Network, an independent investigative journalism non-profit focusing on food, agriculture and environmental health. A longer version of this story appears on TheNation.com.