More lawsuits over "natural"

by Joel Preston Smith and the editors

This article was originally published in March 2014

The number of lawsuits challenging use of the term “natural” on packaged foods has exploded in the past couple of years.

Since the Sound Consumer first reported on consumer confusion over What does natural mean? (October 2011), more than 100 lawsuits reportedly have been filed against brands including Cargill, PepsiCo, Ben & Jerry’s and dozens of others. In general, the lawsuits allege that some of their “natural” claims constitute deceptive marketing.

So far, none of the “natural” lawsuits have gone to trial, according to The New York Times. They have been settled out of court or dismissed by a judge. But many are still in the pipeline.

One result is that food companies are pulling back on using the “natural” claim. According to The Wall Street Journal, only 22 percent of food products and 34 percent of beverages introduced in the United States in the first half of 2013 had “natural” labels, down from 30 percent and 45 percent, respectively, in 2009.

Companies such as PepsiCo and Campbell Soup are among the companies dropping the “natural” label. Barbara’s dropped the “natural” claim from its Puffins cereals after a 2011 investigation found genetically engineered (GE) ingredients. Now most of Barbara’s cereals and cookies prominently display the Non-GMO Project Verified seal.

The meaning of “natural”

A 2010 survey done by the Bellevue-based research firm, The Hartman Group, found a majority of respondents from across the country believed “natural” implied “absence of pesticides” and “absence of herbicides.” Sixty-one percent believed “natural” implied or suggested the “absence of genetically modified foods.”

According to research firm, Datamonitor, only 47 percent of Americans reportedly trust the “natural” label.

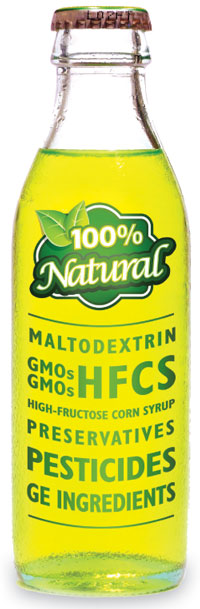

Urvashi Rangan, director of consumer safety at Consumers Union, says “Eighty-six percent of consumers expect a natural label to mean processed foods do not contain any artificial ingredients, but current standards (see sidebar) prohibit only artificial colorings and additives. High-fructose corn syrup, partially hydrogenated oils, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and more still can be used in natural foods.”

Combine these expectations with the finding from the Natural Marketing Institute that two-thirds of Americans believe foods today are less safe to eat because of chemicals used during growing and processing of foods, it’s a recipe ripe for challenge.

The word “natural” is not defined or regulated by the government or any other agency, except by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for processed meat.

Unlike “organic,” no government agency, certification group or other independent authority defines the term “natural” on packaging or ensures the claim is truthful. Buying foods labeled “natural” may not mean anything for avoiding synthetic inputs and toxins used on farms and inside manufacturing plants.

The trouble with “natural,” says Stephen Gardner, litigation director for the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), is that it has no legal definition. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a longstanding policy that “natural” means “nothing artificial or synthetic (including all color additives, regardless of source) has been included in, or has been added to, a food that would not normally be expected to be in the food.” In 1993 FDA stated it would consider defining “natural,” but essentially has tabled the effort.

FDA declines to define “natural”

An FDA spokesperson says the agency has sent several warning letters to companies in the past about use of the term “natural” but even in January, it “respectfully declined” to define it. Three federal judges had asked FDA for guidance in lawsuits against Mission tortilla chips (Gruma Corp.), Campbell Soup and Kix cereal (General Mills). The plaintiffs allege that “natural,” “all natural” or “100% natural” claims are misleading because the foods contain corn grown from unnatural GE seeds.

The judges hearing the cases referred the question of whether foods containing GE ingredients can be considered “natural” to FDA. The FDA sent a letter to the three judges saying, essentially, the agency can’t take on the issue, “because especially in the foods arena, FDA operates in a world of limited resources, we necessarily must prioritize which issues to address.”

High-profile cases

Cargill’s low-calorie sweetener, Truvia, has faced multiple lawsuits during the last couple of years. Plaintiffs say they were misled by Truvia’s portrayal as a “natural” sweetener, when the stevia extract is put through a harsh chemical process, the erythritrol is synthetic and Truvia contains GE ingredients.

The company settled one suit last September, agreeing to pay up to $5 million to nettled consumers who could produce receipts for Truvia products labeled “natural.” Cargill also agreed to remove the stand-alone term “natural” from Truvia-enhanced foods and beverages. Cargill now has rebranded with the phrase, “Adds natural, zero-calorie sweetness.”

Several suits are challenging “natural” claims when the foods contain GE ingredients. Frito-Lay, a brand owned by PepsiCo, was sued in 2012 for labeling its SunChips and Tostitos “natural,” despite being made from GE ingredients, including GE corn and oils (confirmed by lab tests). Reuters says Frito-Lay’s “all-natural” chips also cost more than PepsiCo’s other chip brands. The lead plaintiff had paid an extra 10 cents per ounce for the “all-natural” chips.

Campbell Soup reportedly was sued in 2012 by Florida residents for misrepresenting the GE corn in its soup as “natural.” The suit alleges Campbell’s Soup knowingly mislabeled, fully aware its ingredients were grown from GE seeds.

The Campbell Soup brand, Pepperidge Farm, soon will drop the “natural” claim from Goldfish cracker packaging following a $5 million suit filed by a consumer who objected to use of the term for crackers with GE ingredients.

In the fall of 2010, Ben & Jerry’s took the “natural” claim off 48 products made with maltodextrin and hydrogenated oils, and now uses the phrase “Made of Something Better.” Nonetheless, CSPI has not dropped a class-action lawsuit against Ben & Jerry’s.

CSPI also is co-counsel in a fraudulent marketing class-action suit against PepsiCo’s brand, Naked Juice. The suit alleges that Naked billed its products as “all natural” when the juices contain GE ingredients and synthetic fibers manufactured by Archer Daniels Midland.

In July 2013 PepsiCo agreed to pay $9 million to settle the suit and says it is removing the words “all-natural fruits and vegetables” from the Naked brand until “there is more detailed regulatory guidance.”

Consumer expectations

“It is in large part FDA’s refusal to define natural that the Naked case, and dozens of others, were necessary,” Gardner argues. “An FDA definition would eliminate the ability of the food companies lawyers to whine that there was no definition. However, that’s not true. The word has a meaning to consumers, even if FDA won’t define it.”

Sonya Angelone, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, says the lack of regulation of the term “natural” leaves consumers open to exploitation.

“There are some people who are particularly vulnerable to marketers,” says Angelone, also a registered dietician. “The elderly, in particular, because they’re worried about eating healthy, seem susceptible to nebulous claims like natural.”

“Consumers assume that natural means the product is healthy, or doesn’t have much sugar, or doesn’t have GMOs in it, and so on,” she adds. “As is, the term is misleading.”