Are Puget Sound's tiniest fish in peril?

by Barbara Clabots

This article was originally published in April 2017

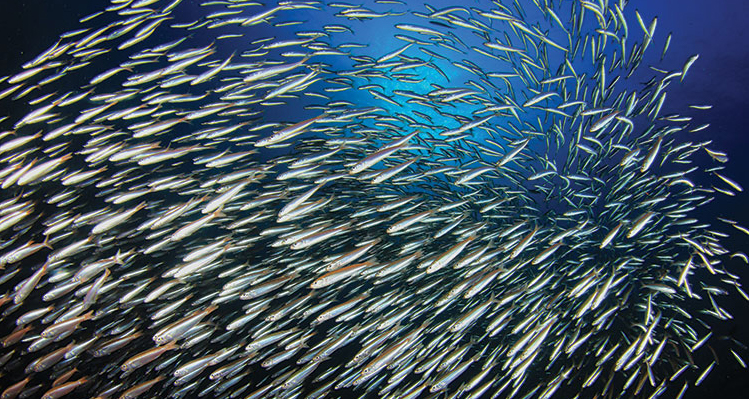

Forage fish — the tiny fish that account for the largest fish populations in Puget Sound including herring, smelt and sand lance — are important to the health of the rest of the aquatic ecosystem. They’re a food source for larger fish including salmon, as well as for seabirds and marine mammals. It’s a reason herring populations are used as an indicator for the health of local waters.

Are these tiny fish in trouble? That’s the question the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) is trying to answer. It’s in the middle of a $2-million, two-year study to determine the status of forage fish in local waters.

Adam Lindquist, a fisheries biologist for WDFW, is one of the scientists studying herring populations. Lindquist and others are studying forage fish populations by trawling — dragging a net behind a boat and hauling up the fish to count them.

Researchers also are documenting public and private beach conditions, and analyzing thousands of beach samples for fish eggs. The types and numbers of eggs are documented and used to update periodically a map showing forage fish spawning habitat around Puget Sound.

This study is filling a knowledge gap for several species. “Herring is the one forage fish we annually estimate an abundance for; for all the other forage fish we do surveys of spawning sites but don’t estimate a population,” said Lindquist.

A 2012 WDFW report on forage fish caused some alarm, as scientists found a 92-percent decline in the herring population at Cherry Point since 1972. Newly released results from the annual Puget Sound Marine Waters Report indicate that 2015 was the worst year on record for two genetically distinct herring populations at Cherry Point and Squaxin Pass.

Mixed results

“We still don’t know why they’ve decreased,” says Lindquist. “Our goal is to monitor and enhance the population, but we’re mostly in a monitoring cycle and don’t know what we can do to boost their populations.”

But Lindquist says that overall, herring populations seem okay. While they’ve decreased in some areas, they’ve increased in others. “If you ignore the Cherry Point data, the rest of the population has been pretty stable since the 1970s.” The follow-up to the 2012 report is expected to be published in summer 2017.

A 2015 study by Correigh Greene from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Northwest Fisheries Science Center found that herring and surf smelt — historically the two most abundant forage fish — have declined by as much as two orders of magnitude in Central and South Puget Sound over the last 40 years. However, the populations of two species — Pacific sand lance and three-spined stickleback — actually have increased.

What’s to blame for the decrease of some fish? In part, shoreline development and water pollution.

“We found that human population density was the strongest predictor of decline in forage fish,” says Greene. “The three species that spawn along the shoreline — sand lance, surf smelt and Pacific herring — have the potential to interact with people. So there’s a concern that shoreline hardening, or armoring, can affect them.” People especially are concerned about the sand lance, says Greene, because they seem to be an important prey source for salmon and seabirds.

Shoreline armoring — once thought to prevent erosion — actually erodes natural beaches and directly reduces the kind of habitat forage fish need to spawn. NOAA research suggests that armoring increases water temperature and is associated with higher mortality rates for surf smelt.

But restricting armoring on private beachfront property has proven difficult. Construction of new armoring has continued largely unabated, at the rate of approximately 1 new mile of armored Puget Sound shoreline each year.

Scientists have identified another impact of urban areas on forage fish: light pollution. Light pollution from the shoreline and the general glow of city lights is making it easier for predators to catch forage fish at nighttime.

Also, spawning sites with little tree cover tend to have lower egg survival rates. “People want views and trees get logged off near beaches — but that might mean there’s less protection for eggs,” WDFW scientist Phillip Dionne told the Kitsap Sun. “With less shade, the eggs might not be staying cool enough.”

State agencies, environmental organizations, local government and Puget Sound residents are taking action to protect forage fish habitat. Scientists and policymakers across the region are coming together to increase evidence-based environmental policies through the Puget Sound Ecosystem Monitoring Program (psp.wa.gov). See the sidebar for ways you can help!

Help protect forage fish

Local policy

Look up your local Shoreline Master Programs (SMPs), written at the city and county level, to provide comments about how to improve habitat for forage fish: www.ecy.wa.gov.

Property owners

Waterfront residents have a unique opportunity to help forage fish through the Washington Department of Ecology’s Green Shorelines program. The program helps property owners restore a developed shoreline to its natural functions. There are grants, tax breaks, and permitting incentives. Visit www.ecy.wa.gov.

National policy

The Puget Sound Federal Task Force, established under President Obama, released a draft of a Federal Action Plan for the recovery of Puget Sound in November (see www.epa.gov).

It’s unclear what will happen under the new administration, but the plan’s intent is to demonstrate that Washington state and nine federal agencies are aligned in their efforts to recover one of the most important waterways in the nation. It’s built around the three major strategic initiatives approved by the Puget Sound Partnership:

- Protect and restore shellfish beds

- Prevent pollution from stormwater

- Protect and restore shellfish beds

Barbara Clabots is a conservation professional with a master’s in Marine Affairs from the University of Washington.