Kirkland PCC expands in new location

By Rebekah Denn

This article was originally published in May 2022

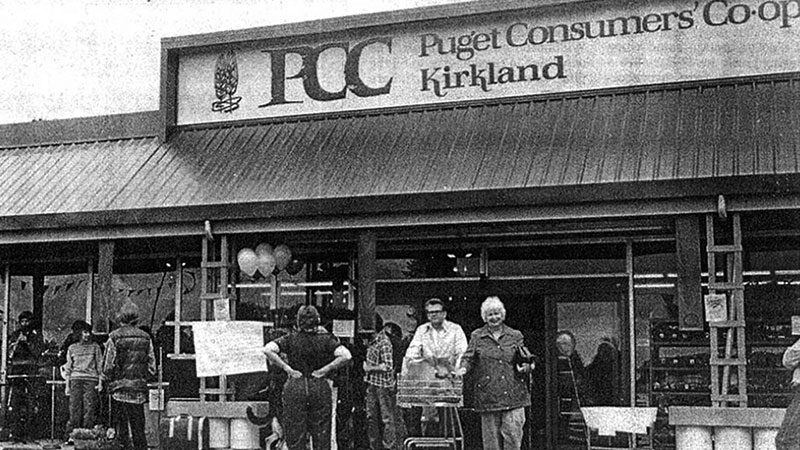

“We are so glad you are here!” shoppers told staff at PCC’s Kirkland store when it first opened on March 16, 1978. “We’ve just been waiting for the store to open…it’s beautiful!”

The original store was PCC’s second location when it opened 44 years ago—without working refrigeration or a lot of other amenities in its first days.

“For many of our customers, members and staff, their first memories of PCC are behind these old walls,” Assistant Store Director Eli Dorr-Fay said in a staff letter as the final day in that building approached.

Earlier this year, the store relocated to a brighter, bigger and significantly updated location less than a mile from its old home. Members and shoppers lined up for opening day March 2 with similarly kind words as CEO Krish Srinivasan and Store Director Mike Stampalia sliced open a ceremonial cabbage instead of a ribbon.

The storefront at 430 Kirkland Way is about 19,000 square feet, 30% larger than the original. All staff members from the old store were offered jobs at the new location.

Features of the new store include a pizzeria with hot slices and made-to-order whole pies, a hot food bar with more offerings and a salad bar featuring organic produce, an expanded bulk department with closed-loop bulk body care items (where companies can reuse packaging), and a full-service meat and seafood counter.

Store staff will continue to work with Kirkland Hopelink and Community Resource Network (CRN), its partners for more than 15 years through PCC’s Food Bank Program—a program originally founded at the Kirkland store.

It will be the fifth co-op location to pursue the Living Building Challenge (LBC) Petal Certification by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), the world’s most rigorous green building standard. To meet these standards and in alignment with the co-op’s vision to inspire and advance the health and well-being of people, their communities and our planet, steps included:

- Recycled & Repurposed: Many of the store fixtures that hold the co-op’s high-standard products were built with recycled materials and repurposed equipment from other PCC stores when possible, including shelving, racks, tables and even an ice machine.

- Reduced Energy: The new store was designed to have more than three times the amount of windows—from just over 400 square feet to now more than 1,400 square feet—which brings in more natural daylight and significantly reduces indoor lighting energy use.

- Low-Impact Refrigeration: The new Kirkland store joins the co-op’s Ballard, West Seattle and Bellevue locations in using a carbon dioxide refrigeration system, which boasts 3,000 times less of a global warming potential than the synthetic refrigerants used in most grocery stores. PCC continually works to reduce refrigerant leaks across its stores and will begin to phase out high-impact refrigerants at older stores with lower impact and climate-friendly alternatives. Of the approximately 38,000 supermarket locations in the U.S., less than 2% of existing stores use natural refrigerants (like a carbon dioxide system) exclusively.

- Public Art: The store features five columns with hand-glazed ceramic tiles in the store’s seating area by artist Mary Iverson representing “World Tablecloths.” Each column features a tablecloth design inspired by the textile patterns of a unique culture that is part of the community makeup of Kirkland: Coast Salish, Nordic, India, Japan and England.

“A tablecloth is the underlying fabric that makes a meal special, weaving colors and symbols with family traditions,” Iverson said. “PCC is such a special part of the community: as a space for neighbors to gather in or the source of the food they bring home to their tables to serve friends and family. I appreciate the opportunity to bring this work to the Kirkland community and hope to inspire their table conversations.”

Sunflower Center

The Kirkland co-op actually wasn’t planned as a PCC. Organizers envisioned it as “Co-op East,” part of a nonprofit created through the Bellevue Environmental Group. Half of the “Sunflower Center” in a former grocery store would be taken up by that co-op, according to newspaper accounts at the time. Half would be a natural-foods restaurant, with eventual plans to add a community center, farmers market, consignment shop and classes.

“People who would use an Eastside co-op more than PCC are encouraged to transfer their memberships to the new store,” directed a 1977 article in PCC’s newsletter, the predecessor to the Sound Consumer.

Mimi Simmons, one of the original planners, remembers making weekly trips across Lake Washington to PCC’s then-single store in the Ravenna neighborhood. Foods that are easily accessible now “simply weren’t available elsewhere” back then, she recalled in a written remembrance. Eastsiders dearly wanted a food co-op in their own community.

“As a volunteer, my job was to call PCC members who also lived on the Eastside, and potentially interested others, soliciting $60 memberships in Co-op East. Despite our campaign, including many hours of calls from a lonely desk in the empty store, we were not able to find enough members,” she wrote.

That contributed to another roadblock: Establishing the store would have depended on a significant loan from PCC. In a long debate that stretched past midnight, board members decided against providing the money, according to the Sound Consumer’s account. While it was “hard to convey in a little article the complexities of all the issues before the Board,” concerns included Co-op East’s planned budget, skepticism about “a practical commitment to worker self-management and the politics of cooperatives,” and “an unacceptable risk of store failure.”

The board voted instead to survey PCC members about purchasing all the assets and liabilities of the company. In an in-store questionnaire, 73% of 782 members said yes. The purchase went through, boards of both organizations approved the sale—“followed by a sparkling cider toast”— and Co-op East was reimagined as PCC Kirkland.

“COME SEE PCC’S NEW STORE!” read the 1978 headline.

Simmons became one of the first staff members—her 39-year PCC career included serving as the co-op’s longtime customer service manager—and remembered the community’s commitment to that location.

For packaging parties, “Recipes were included in the family-sized bags of beans and rice. Teams of volunteers prepared these donations for our local food bank. These work parties were the first versions of PCC’s decades-long, ongoing donations to those in need of food.”

A different world

It looked a lot different in the early days, recalled Roxanne Green, who joined the staff in 1983 and retired 36 years later.

“Our bulk system was the big green garbage cans with black liners. We had beautiful merchandise shelves made out of two-by-fours that Read Handyside (one of the first Kirkland employees, now working at the Fremont PCC) actually built.” It was a small staff, and “we all did whatever had to be done.”

Meat was sold through “The Meat Shop,” a separate cooperative, at a time when members hotly debated whether PCC should even sell meat. “Even sugar was a big deal.”

Stores had councils with member as well as staff representatives at the time. John Affolter, who had founded PCC as a food-buying club more than 30 years earlier, was a member of Kirkland’s council.

“He was an older gentleman then and was really nice—he always brought a tofu casserole and always gave his input,” Green recalled.

Some members, for instance, had wanted to expand into outside product lines like tires. “He said no, we always had those ideas, but we realized you stick with what you do best,” Green said. Simmons recalled how Affolter always arrived “with ideas and lists of suggestions typed on his signature crinkly thin paper.”

A remodel added the deli and some extra space in 1985, and the old store had looked about the same since then, Green said. Her work included everything from cashiering to serving as assistant store director, but overseeing health and body care products was her real love. She helped screen products and set guidelines for which products PCC should carry. For many years she served on the board of the Natural Products Association, which puts on trade shows locally and works nationally to support legislation and industry regulations. She was president of first the local and then the national board. That’s the sort of work that kept her there for so many years.

“PCC really makes a difference in a lot of people’s lives, and for a lot of us long-timers that was our mission, that’s what we did, what we do,” she said.