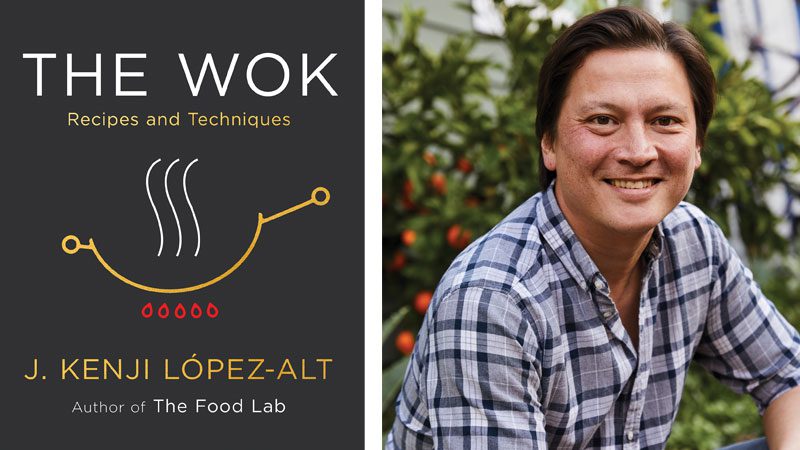

Fast, fun stir-frying with J. Kenji Lopez-Alt and “The Wok”

This article was originally published in July 2022

“Culinary nerd” J. Kenji Lopez-Alt has brought the science of great cooking to readers for years through his column in SeriousEats.com and his definitive cookbook “The Food Lab.” Since moving to Seattle with his family in 2020, he’s chronicled his home meals in a YouTube cooking channel and shared tips on great regional restaurant eats on his Instagram page. His latest book, “The Wok: Recipes and Techniques” (W.W. Norton, $50) has been billed as the year’s biggest cookbook release, a 4.7-pound, 672-page—but approachable and friendly—guide to this phenomenally useful cooking tool. An excerpt from the book follows, and Lopez-Alt will teach a PCC cooking class in July (sign up (waitlist only)).

Many things can be called fast, versatile, and fun. My old Kodak Pocket Instamatic. Transformers.

Bo Jackson. But add delicious to that mix and suddenly your list gets a whole lot shorter.

Stir-frying is fast. Most stir-fry recipes take under half an hour start to finish, and that’s including prep time. The actual cook time of most stir-fries is just a few minutes.

Stir-frying is versatile. You can stir-fry meat. You can stir-fry seafood. You can stir-fry Asian vegetables or Western vegetables or tofu or rice or corn or mushrooms or lettuce or nuts or noodles or virtually anything that’s at least semisolid and edible.

Stir-frying is fun. I mean, I think it’s fun. If you enjoy activities that are simple enough for a first-timer to get good results, but also reward you greatly as you practice and improve your skills, you may think it’s fun as well.

Stir-frying is delicious. You know it, I know it, anyone who’s eaten at even a mediocre Chinese chain restaurant knows it. Stir-fried vegetables retain their bright, fresh crispness and color. Properly marinated, massaged and stir-fried meats are tender and packed with flavor. (We’ll talk more about the importance of massaging meat later.) Stir-fried noodles and rice pick up a flavorful char and, when you get really good, some of that elusive wok hei—the smoky aroma you find at good Chinese restaurants. (You’re gonna learn how to get it right at home, no matter what kind of stove you’ve got.) Stir-fries incorporate sauces, condiments, spices, pickles and aromatics that pack flavor into foods quickly and easily, which means you can build complexity and depth into a dish even on a busy weeknight.

Of all the techniques I’ve learned over the years from all over the world, stir-frying is the one I’d take with me to the desert island. It’s how the plurality of meals in my life have been cooked, and I imagine it’ll stay that way until I die.*

The Anatomy of a Stir-Fry

More than anything, stir-frying is about technique. In a November 2018 study led by David Hu, a professor of fluid dynamics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Hu used computer software to track and model the motion of fried rice in a wok as it was tossed by professional Taiwanese chefs. What they found was that the motion of a stir-fry could be broken down into oscillations that last about a third of a second.

Within each of these oscillations, there are four distinct phases, each composed of translation motion (pushing and pulling the wok farther and closer) and rotational “seesaw” motion (pushing the handle up and down so that the wok pivots where it makes contact with the burner ring) that are slightly out of phase with each other, resulting in a back-and-forth rocking that causes food in the wok to leap toward the chef in a cascade, effectively mixing it. Here’s what those phases look like in slow motion:

PHASE 1. With their hand firmly on the handle or the side of the wok closest to them, the cook pushes the wok forward while it is tilted downward away from them.

PHASE 2. As the wok gets close to its maximum distance away from the cook, the cook will begin to push down on the handle, causing the back edge of the wok to begin tilting back upward.

PHASE 3. While the back edge of the wok is still rising, the cook will begin pulling the wok back toward them. During this phase, the rotational motion and the rapid translational acceleration cause the food to leap. The food near the top lip of the wok will feel the greatest acceleration, while the food closer to the base of the wok will feel less. This is what causes the cascading waterfall effect.

PHASE 4. The cook continues to pull the wok toward them, catching the food. Just as the wok reaches its point closest to the cook, the cook lifts up the handle, tilting the wok downward again and getting ready to push the wok forward to repeat Phase 1.

So, in effect, each rocking motion occurs in slight anticipation of each translational motion. It is, in many ways, similar to the way I try to teach my daughter to pump her legs on the swing: To do it effectively, you need to straighten your legs and lean back just before you reach the apex of your back swing, and you need to lean forward and bend your knees just before reaching the apex of your front swing.

What Happens When You Toss?

As Grace Young explains in her book “Stir-Frying to the Sky’s Edge,” the term stir-fry is misleading. Stirring, in the Western sense of moving things around the bottom of a pan using a spoon or spatula, is not what you want to do in a wok. “Tumble-fry” or “toss-fry” would be more accurate. Central to the technique of stir-frying is tossing food through the air. Why is this so vital?

The steam that evaporates off food and into your kitchen actually contains a huge amount of energy. Stir-frying takes advantage of this by recapturing some of that energy, which in turn speeds along cooking and helps develop intense flavors. In “Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking,” the authors demonstrate how a column of hot air and steam will rise up around the back of a wok. As you stir-fry, you toss the food through this steamy air. The steam condenses on the surface of the food, depositing “formidable amounts of latent energy,” which rapidly heats it. As it falls back into the wok, which has now had a chance to recover some of its heat energy, that surface moisture is revaporized and the cycle continues.

This is why stir-frying is such a quick cooking process and why the shape of a wok is so important: it allows for dramatic tossing.

Does your food more often end up in your stove grates or on the floor when you try to toss it? Does it seem like no matter how vigorously you stir the contents of your wok, nothing seems to cook evenly? Don’t worry; you’re not alone! Like riding a bike or trying to plug in a USB cable, stir-frying is one of those things where you have to keep at it until it suddenly just clicks. If you stir-fry a few times per week, it should come quickly enough, but if you want to speed up the process (and perhaps save yourself from a few hot or greasy spills), the best way I know how is to fill your wok with a cup of dry lentils, beans or rice.

Here’s the basic process, though images and words can only get you so far—practice is the only way you’re going to get it.

MOVE 1 • Holding the handle of the wok, tilt the wok slightly away from you.

MOVE 2 • Push the wok forward in a smooth, relatively gentle motion, keeping it tilted away from you the whole time.

MOVE 3 • Just before you start pulling the wok back toward you, tilt it upward by pushing down on the handle. You should begin pulling it back toward you with a quick jerk about halfway through its upward rotation. This should send the food flying up into the air, with a parabolic trajectory that sends it back toward you.

MOVE 4 • Catch the food in the wok as you continue to pull it backward, then start to tilt it back down by lifting the handle just before you start pushing the wok forward again to repeat the cycle. As you practice, you’ll find a natural rhythm of tossing and catching that varies slightly depending on how much food is in your wok, but it’s typically two to three cycles per second.

*Or at least until I get one of those awesome live-fire grills they have at fancy restaurants with the pulleys on the sides that let you lift the grates up and down. Those things are so cool.

Cook with J. Kenji Lopez-Alt

Join J. Kenji Lopez-Alt for a PCC cooking class in July connected to his new book, “The Wok.” He’ll share techniques, stories and recipes for mapo tofu, cucumber salad and Chinese American kung pao chicken. The book is also available in all PCC stores.

Sign up for PCC cooking classes here.